THE DAY THE PENNY DROPPED

by N.J.Spencer, 2nd March 2023

Both my parents were artistically inclined, my father more practically so. He had trained at art colleges in Leeds, Bradford and Paris in the nineteen-forties, then worked as a lecturer before becoming a secondary-school art teacher and, late in his career, teaching at Dumfries High School. My mother loved to theorise about many things, and colour was one of them. She in fact painted more at home than my father did, which was no great achievement because I only twice saw him paint at home.

Being brought up in an art-conscious family persuaded me never to be dismissive of art. As a child I knew my parents considered art to be something of importance and to be taken seriously. After all, it was my father’s profession, and his skills as an artist and teacher paid for our home and everything we had.

Despite being imbued with this sense that painting was not a frivolous affair, and that something might be lost if all painters were swept into the dustbin and replaced by photographers, I really did not see what all the fuss was about. I did not see much purpose to painting beyond the self-indulgence of the artist, and I did not see why great artists were revered. Surely, if one was attempting to depict a real object, then a photograph would make a better and quicker job of it; and if one was not depicting a real object, then was painting very much more than creating home decor? Such attitudes towards art were common.

Regardless of this level of doubt as to the value of art, I nevertheless persisted in visiting galleries and looking at works of art in books, there being no internet in those days. I would find myself touring a gallery, liking this and not liking that, but still it seemed to me that true art-lovers like my father had a power to appreciate something in a painting that I lacked a faculty to apprehend. I was sure I was missing something.

It was in about nineteen eighty-five, after I had been looking at paintings for twenty years with no greater understanding than I had ever had, that I happened upon an extraordinary painting in the National Gallery in Edinburgh. There was nothing grand about it; it was of modest dimensions; there was neither dramatic subject matter nor narrative; it had no figure or outstanding motif to catch at the attention; one might have said that there was nothing remarkable about it at all, just another among thousands of landscape paintings. But as soon as my eye settled on it, I was drawn to this painting like iron to a magnet.

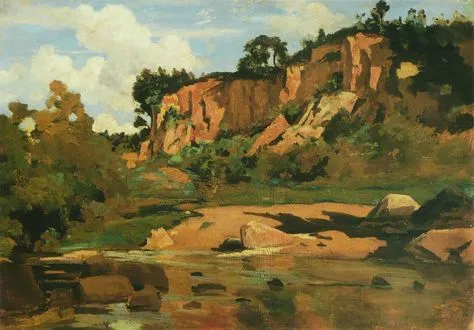

During the next fifteen minutes or so that I spent gazing at this gem, everything about the point of painting, the purpose of painting, and the value of painting, fell into place. It was a revelation. I read the information card that was mounted on the wall next to the painting and memorised the artist’s name, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. I had never heard of him. There was something captivating about this painting of the warm, honeyed rock, the pale and dark olives of the trees, and the freshness of the cloud-studded sky that had me basking in the Italian sunshine with a great sense of tranquility and contentment. The tones and colours were placed and shaped in such good order, that nothing seemed artificial or contrived. At the same time, it was a painting that, despite its sublime accomplishment, did not try too hard. There was a lovely ease about it.

Corot’s painting turned out, for me at any rate, to be far more than just a scene of some pleasant rural spot of one hundred and fifty years ago. It had an effect as when one hears a piece of music that one has heard many times before, but on this occasion played by a master musician whose performance says “This is how it can be done. This is what music is about.” One knows straight away that one has heard something remarkable, something set apart, something from the hands and spirit of a maestro. So it was with this painting by Corot. It seemed to say “This is how painting can be done. This is what painting is about.” Well, what is it about? I can only conclude that when a great artist picks up a brush, he is able to evoke through a painting something that is about much more than the painting itself — and that is about all I can say on the subject without straying into fanciful realms.

I suppose one could call this encounter with Corot an enlightenment, for looking at art was never the same afterwards.